As a young lad I used to cycle, along with two of my chums on the tiniest of bicycles, through Glasgow to the library every week. We had bags of the books we were returning dangling over our handlebars. Each week brought new enthusiasms.

I remember one week we wanted to become detectives and so sought out any book on how to identify fingerprints. Bliss and happiness. This huge, to our eyes, building was full of every book you could ever need. What we didn’t know, at the age of eight, was from where it had come.

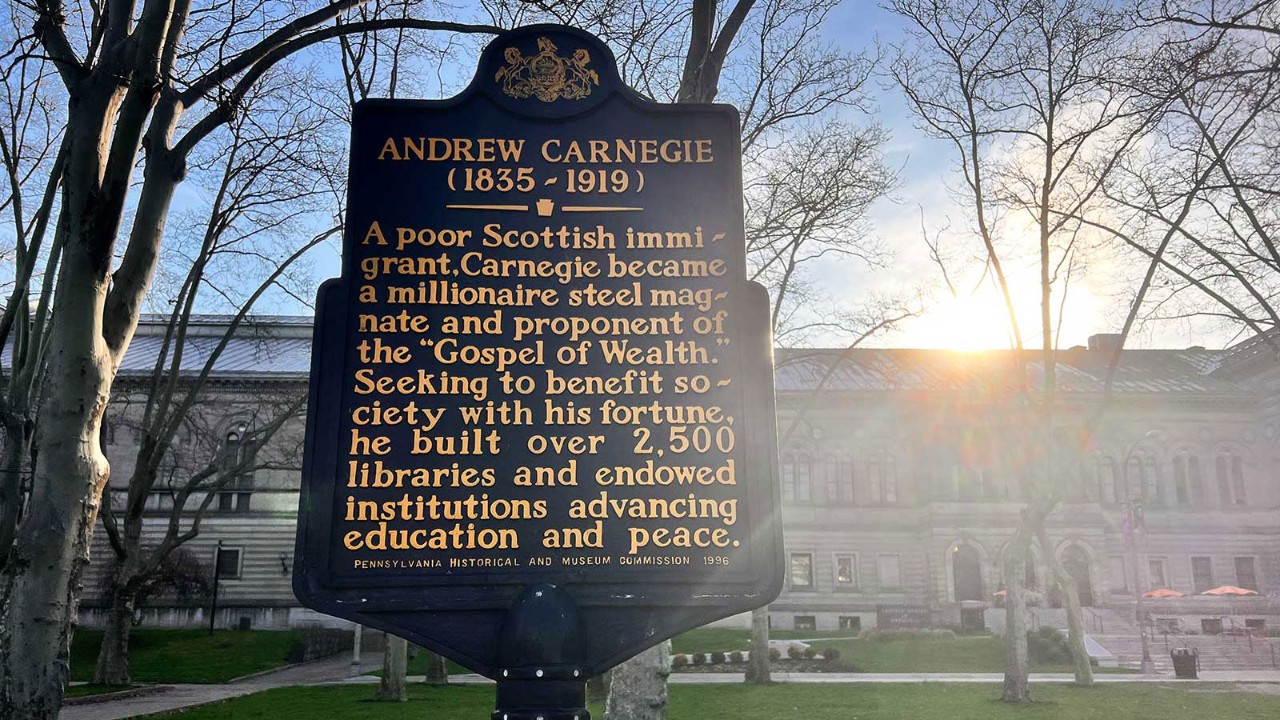

Like so many Scottish schoolboys of that time we were using a Carnegie library, one that had been created out of the money donated by Andrew Carnegie, the fabulously wealthy steel magnate of his time, who is now best remembered for one short sentence that he wrote in 1889. In an essay on wealth, he said: ‘The man who dies rich dies disgraced.’

The bump in literacy that Carnegie created is immeasurable

He had been born in Scotland, in Dunfermline, but made his staggering fortune in the US. And one legacy of his wealth is the upwards of 2,500 libraries around the world that became the springboard to literacy and employment. It could be seen as a Scottish trait. The Scottish poet Robert Burns got his education because the local farmers, including his father, banded together to fund a school for their children over 100 years earlier.

Transformative power

It is hard to quantify the bump in literacy that Carnegie and his ilk created. It is immeasurable really. But the upward trajectory in the spread of knowledge, expertise and understanding transformed lives around the world for generations.

These days Bill Gates, the founder of Microsoft, aims equally to transform lives through charitable trusts, but the focus is on body, not mind. He recently announced that his foundation, set up 25 years ago, while having funded medical research to the extent of US$100bn, would now accelerate its efforts.

It is not literacy that Gates pursues but global health

The original intention was to distribute the foundation’s funds across several decades after his death. Now the intention is to distribute it all by 2045 – an expected further US$200bn, figures that Carnegie would approve of.

Times change though. Interestingly, it is not literacy as a way of liberating vast numbers of people that Gates pursues, but global health. His foundation talks of medical advances, but it is the same principle. The poorer in societies around the world should have greater chances.

So the Gates Foundation focuses on infant mortality, vaccines and other measures to try to close down the most prevalent infectious diseases and thereby, not that differently from Carnegie, give people the chance to flourish over long lives.

Shared goal

The aim is the same, the measures to bring it about are different. The mission in Gates’ words, is ‘to create a world where every person has the opportunity to live a healthy, productive life.’ Much of this, in the day to day, goes unnoticed. The news is full of disasters and worries rather than the possibility of hopeful outcomes. It is how it works.

But quietly, if you listen, things do change. The foundation run by Sir James Dyson, engineer and innovator, has, a friend of mine reports, among many other projects, transformed the nature of cancer treatment in and around the city of Bath in the UK.

The important principle is to make a difference before you exit

And I recently came across a couple who have assiduously built up an art collection in their home and which, in due time, will be bequeathed, both house and collection, to a grateful gallery.

You don’t have to be eradicating disease. Lesser measures can still bring joy. The important principle, as Carnegie made clear, is to make a difference before you exit.