The economics of the sport of cricket can seem very strange. Completely contradictory models seem to work alongside each other.

On a Saturday in August this year, a seat at the top of the vertiginous new Compton Stand at Lord’s cricket ground in London would have set you back £155. On the following Saturday, it cost £30. On both occasions, the ground was completely sold out. Where is the economic logic in that pricing?

The answer, of course, is that the financial logic was very different for each day. The first Saturday, with its astronomically high price, was the Test match between England and India. The second Saturday was the Finals Day of The Hundred, the shortened version of cricket launched this summer in England – though paradoxically, with a double-header of two games, the playing day was longer. So why the pricing disparity?

Top teams vs loss leader

Simple. The first Saturday was one day out the five days of the Test match between two of the top teams in the global cricketing world. Hard-fought and keenly followed by passionate supporters – particularly on the Indian side – you could probably have doubled the prices and still sold out, though the outrage at such prices would have been loud.

The range of people who follow cricket can’t be pigeon-holed, and that is why the game’s economics differ so widely

The second Saturday was effectively a loss leader. This was the first year of The Hundred, the English cricket authority’s attempt to wrest back financial supremacy from other global cricketing leagues, most notably the Indian Premier League, which has flourished in the financial powerhouse that is cricket in India.

Some £40m odd of marketing and other funding had been put into the effort to get The Hundred off the ground.

A reasonable number of the games were shown to huge audiences on free-to-air terrestrial television for the first time in 16 years. The verdict on whether it has been a success has been equivocal.

As a short form of the game, it is remarkably similar to the long-established T20 domestic competition, except that it has the budget to fund much more razzamatazz, from DJs directing the crowds at every five-minute break in play to incessant efforts to exhort small children to hit a ball into the crowd or to decide whether a Mexican Wave should be initiated, and live music performances at every break between innings.

Quite apart from the cricket in the background, it provides a full-on entertainment experience at all times.

Change for the better

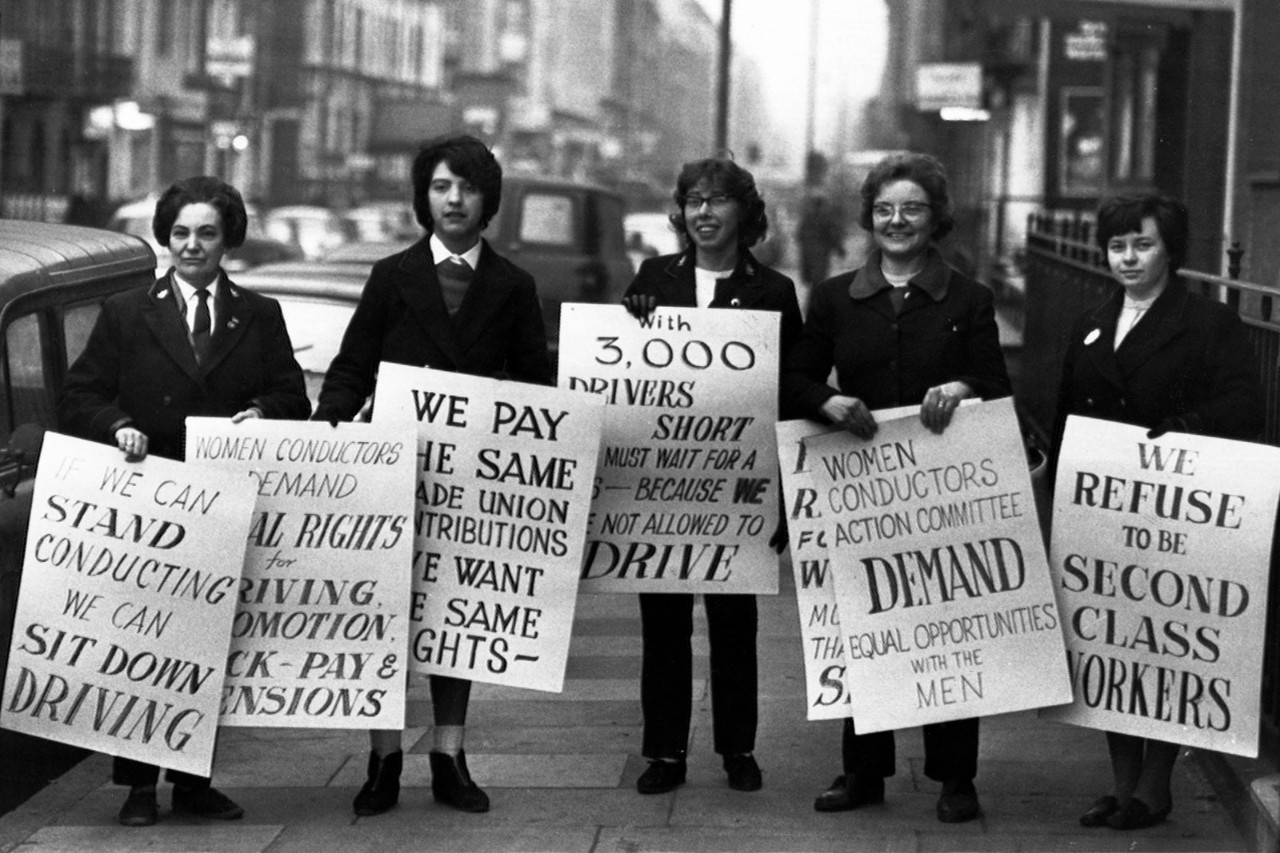

The Hundred may not prove to be the long-lasting success that the organisers crave. But it has brought about one change that will last. There have been effectively two competitions: one for women and one for men. Often, there have been two games per day, one women, one men – a joyous double-header of contrasting skills.

And women’s cricket has been shown to have a secure and enthusiastic following, with attendance records for games being regularly broken. That is probably where the new market really is, though, to be fair, the existing short-form T20 competition has always drawn a sizeable number of women as well as small children to its games.

At the same time, the county championship, with its longer, more cerebral and sociable atmosphere, but on whose foundations the rest of the English game depends for its emerging talent, feels itself pushed to the margins. Perhaps, contradicting the new economic model, it is due a slice of the marketing budget.

Breaking tradition

Meanwhile other cricketing traditions are being broken. Early in The Hundred competition I was on the top deck of the Pavilion at Lord’s and found myself sitting near a previous chief executive of the MCC, the venerable club that owns Lord’s. Was he wearing a jacket and a tie, normally one of the inviolable rules of the club? No, he was not. And he was surrounded by children – again, a demographic normally barred at all times from the hallowed Pavilion precincts. Everyone seemed very happy.

It is one of the clichés of cricket that it is hidebound and unchanging. This has, like most clichés, never really been true.

A few weeks later, I was on the top deck of another hallowed Pavilion, at the Oval cricket ground in south London, for another Test match between England and India. For a couple of days, I was sitting alongside a father and his teenage son, both fervent and erudite India supporters. On the Saturday evening, I asked the son if he was going to be there on the Sunday, for the fourth day of what was turning out to be an enthralling and ever-changing match. No, he wasn’t.

On the Sunday morning he was flying out to the US. He was off to take up his undergraduate place at a very distinguished university to study a branch of medical science and with the hope that it might lead, eventually, to a doctorate. It reminded me once more that the sheer range of people who are fascinated by cricket and follow it closely can never be pigeon-holed into just one version of the game. And that is why the economics that underpin cricket can differ so widely.