Data from the World Trade Organisation (WTO) shows that since the 2008 global financial crisis, there has been a steady increase in the use of restrictive trade measures. The US has been leading the charge, but developing economies such as India and Indonesia have also been relatively prolific users of such measures. The greater orientation towards protectionism thus went beyond just the actions of former President Donald Trump.

Unfortunately, the tendency for political leaders to resort to inward-looking economic policies such as protectionism seems to be growing.

Domestic instincts

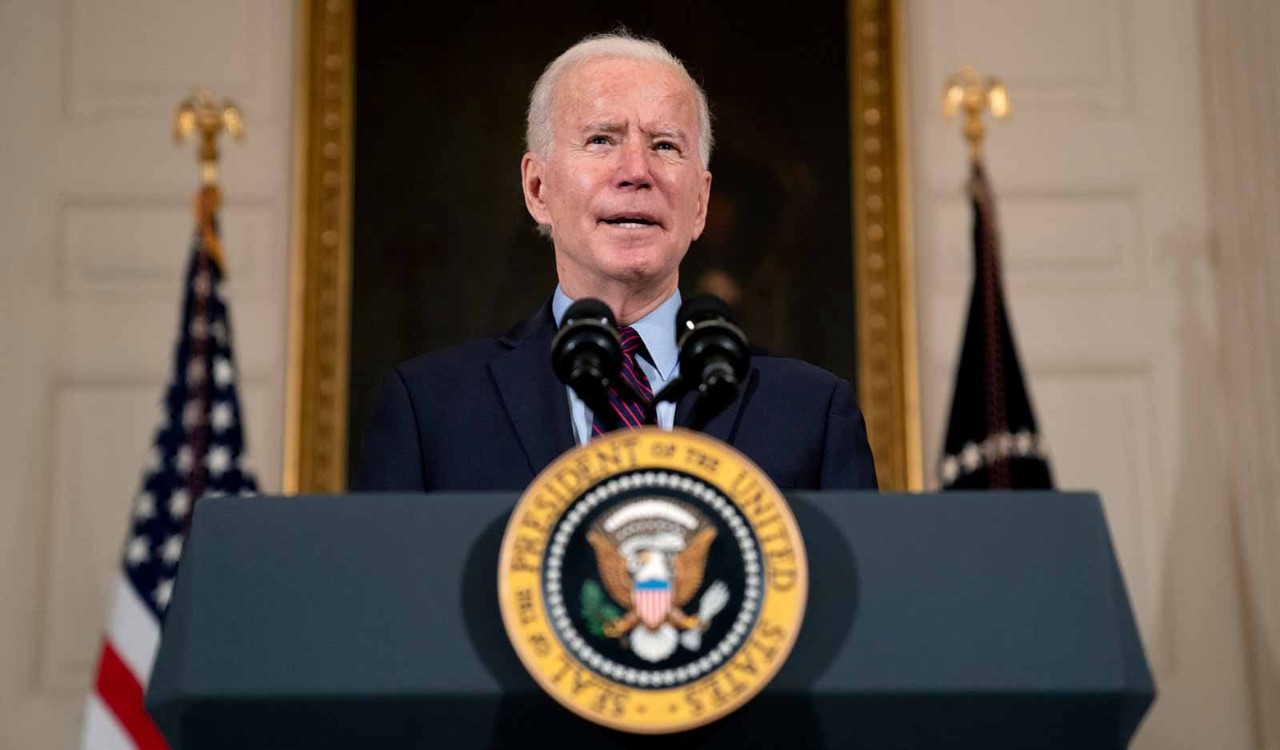

In the US, for example, President Joe Biden has indicated that he will retain some of the trade measures imposed by his predecessor against trading partners. His political priority is to cement his popularity in so-called ‘rust-belt’ states by trying to bring manufacturing back to those areas. His early actions – for example, on tightening rules on government procurement to ensure more American goods are bought – are an indication of where his trade instincts lie.

China, too, is getting warier of depending on trade. President Xi Jinping is advocating a strategy called ‘dual circulation’, under which both external and domestic demand are emphasised, seemingly a shift away from the export-oriented strategy of the past 40 years.

Chinese policymakers seem to prefer greater self-sufficiency in key areas such as semiconductors, and for more of the supply chain in high-value industries to be within China. Similarly, India’s leaders appear to doubt whether India can be competitive enough in the near term to benefit from trade opening. Prime Minister Modi’s policies seem to prioritise domestic production and abjure further trade opening.

The Covid-19 pandemic has also made countries and companies realise that they had under-estimated the importance of resilience of supply chains in key products such as medical equipment and medicines. It is quite likely that, in future, countries might mandate that a high proportion of essential items must be produced domestically.

The pandemic has made countries and companies realise that they had under-estimated the importance of resilience of supply chains in key products such as medical equipment and medicines

Similarly, companies will want to bring some parts of their supply chains to their home base so as to improve resilience. These changes in strategy would slow the growth in trade.

Finally, advanced manufacturing processes such as 3D printing are facilitating the automation of previously labour-intensive production, allowing such goods to be viably produced in countries with high labour costs. This could result in more production being ‘re-shored’ or brought back from low-cost locations to developed countries, reducing the need for trade.

WTO boost

On a more positive note, President Biden is expected to support the global trade regime, which has the World Trade Organization (WTO) at its heart. His administration is likely to cooperate with other WTO members to resuscitate the WTO’s Appellate Body, which ceased to function because the Trump administration systematically vetoed new judges.

Already under Biden, a compromise has been reached to break the impasse over the WTO’s new leader, reflecting the president’s more constructive approach to multilateralism. This is important because a well-functioning WTO will better protect small trading nations.

Another reason for optimism is that countries still have an appetite for multilateral trade deals that result in more trade opening. The recently concluded Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, for example, brings the 10 South-East Asian economies together with China, Korea, Japan, Australia and New Zealand to create one of the world’s largest trade blocs.

The Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership, which imposes more rigorous conditions for membership, is now attracting more applicants. The UK has just formally applied to join while China, South Korea and Thailand are reported to be actively preparing to apply as well. Multilateral trade deals are very much still alive and kicking.

What all this means is that trade volumes may not grow as vigorously in the coming decade as they used to. However, even with some headwinds from protectionism and the reconfiguration of supply chains, trade will continue to be an engine of growth for much of Asia.