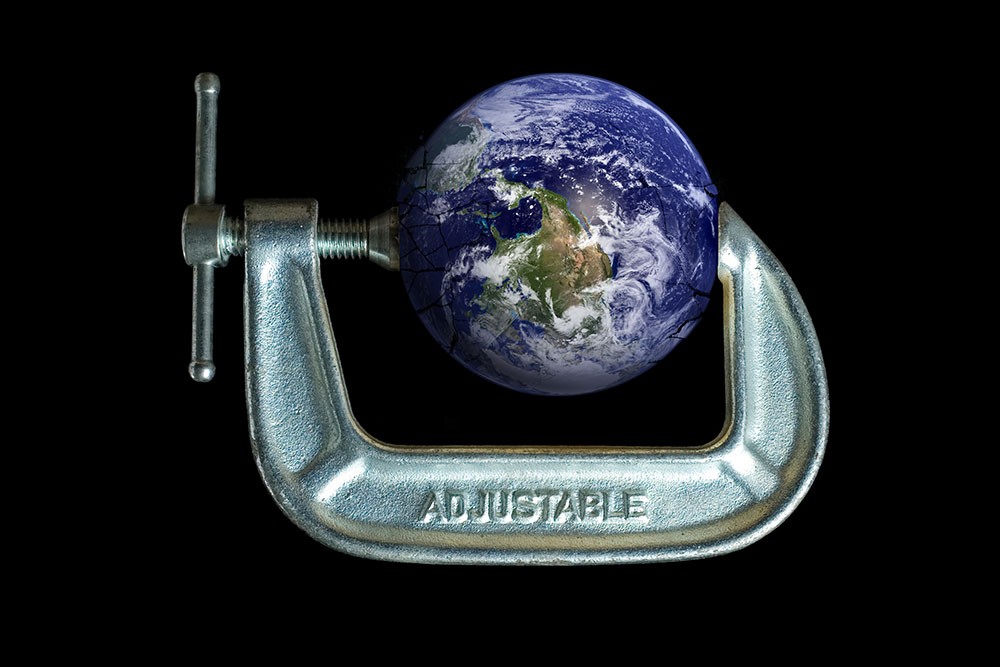

Public finances around the world are facing strains like never before. But as central governments continue to battle with competing demands over healthcare and the economy, it is local governments that are facing increasingly difficult decisions.

Often bound by legal restraints imposed by central government, these local bodies are expected to deliver frontline services, while having to cope with massive reductions in local revenue brought about by lockdowns and economic slowdown.

It is an unenviable situation – on the one hand, local governments are expected to provide services as demanded by central government, but on the other hand they have to go back to these central governments to ask for the budget with which to do so. As such, a spotlight is now being shone on intergovernmental transfers, the process by which public finance is delivered to the right place at the right time.

Here, AB speaks to two finance professionals about their personal experiences and how they are managing to balance the local books.

Challenges in Kenya

Andrew Kubo Mlawasi ACCA is an executive member for finance and economic planning in Taita-Taveta County, 236 miles south east of Kenya’s capital city Nairobi. It is home to a population of more than 340,000, as well as the Tsavo National Park.

‘This crisis has highlighted the need for a new deal for cities as the world continues to urbanise’

The county is one of 47 such jurisdictions in Kenya, all of which are required to supply annual budget proposals to the national government to cover the fiscal year, which stretches from July to June the following year. These budgets cover development needs, such as capital expenditure on schools and hospitals, as well as recurring costs, such as salaries.

As Mlawasi explains, the source of the finance is threefold: an equitable share from national government, calculated through a set formula; revenue sourced locally (levies, fines, etc); and donor funding from bodies such as the EU, World Bank and NGOs, such as World Vision.

In addition, other grants are available in specific areas, such as road maintenance.

‘In a normal year, around 70% of the budget goes on recurring expenditure, while 30% goes towards development and capital spending,’ explains Mlawasi. But when Covid-19 struck in March, the area went into lockdown, including the national park.

‘There were no tourists, the hotels closed down, so there was no income,’ he says. ‘We looked to national government, but they couldn’t collect taxes either, which led to a problem with the equitable share. Monthly disbursements were automatically delayed, which created an issue over salaries and paying service providers, such as the power and utilities companies.’

At the same time, the health crisis created additional demands for isolation wards, PPE, and all the other necessary equipment and drugs. ‘There was no way we could finance that,’ Mlawasi says.

He was forced to make a supplementary budget, which involved collapsing most departments except health and finance. This additional money went towards paying the salaries of local government workers and tackling specific Covid-19 issues.

In total, Mlawasi received an additional $720,000 (£557,000) in two intergovernmental transfers, together with $45,000 from the EU. This provided a cushion, but only up to June. He now awaits additional transfers for July, August and September.

‘The budget has been approved for 2020/21, although we are now awaiting approval from the president to approve distribution, but this has been delayed,’ Mlawasi says. ‘The national government needs to take stock of how much tax it has raised as there will have been a big dip in revenue. The government is now trying to come up with a new formula, but every county is lobbying to get more.’

Coping in Canada

Gary Kent ACCA is commissioner of corporate services and CFO of Mississauga, on the shores of Lake Ontario. It is the sixth largest city in Canada, and the third largest in the Great Lakes province of Ontario. It has a population of more than 780,000. If you were currently permitted to fly to Toronto, you would land in Mississauga.

But during the Covid-19 crisis, Kent’s biggest financial problem has been the loss of transit revenue – lost fares paid by commuters who used to travel to work but have stayed at home during the crisis have left Kent with a CAN$100m (US$76m) hole in his budget.

‘Normally transit income accounts for 17% of our budget and this loss is creating a big pressure,’ Kent explains, adding that although property tax creates a safety net, it cannot be increased. ‘I cannot budget for a deficit, so we are having to aggressively manage the situation.’

‘Local governments globally are running cities in the 21st century with 20th century tools’

Fortunately, Canada is ‘fiscally strong’, but even so there have been delays in transferring additional finance from central to local government. And even though funds are now becoming available in two waves of the Canadian Safe Restart Agreement, Mississauga has been forced to lay off over 2,500 temporary staff – one third of its headcount – and implement a full-time hiring freeze. ‘We’ve had to look at what we can slow down or cancel,’ he says.

He is also concerned about ‘echo years’. From day one of the crisis, Kent understood it would not be just about 2020: ‘We are budgeting for the challenging times ahead. Local governments globally are running cities in the 21st century with 20th century tools, and this crisis has highlighted the need for a new deal for cities as the world continues to urbanise.’

‘We have more than 300 lines of business that engage with our citizens – it is surprisingly complicated and vulnerable.’

For more information

Find resources to support ACCA members in the public sector